What is reportage? What is art? Where does the story of reality pass through?

by Salvatore Garzillo and Gabriele Micalizzi, co-creators of the exhibition “de bello. notes on war and peace” at gres art 671

When we started thinking about the collective exhibition at gres art 671 - “De bello. notes on war and peace” - I thought about my many “notes on war and peace.” About the diaries I had accumulated over the years, full of stories and drawings.

I had just returned from Ukraine, where I had spent a few months as a reporter covering the beginning of the Russian invasion and its development. In addition to doing my job as a journalist with “classic” reports, I drew a lot. I thought about how many strangers I had written about during this trip and how strangers had actually become part of my life. So where is the line between the unknown and the known?

* * *

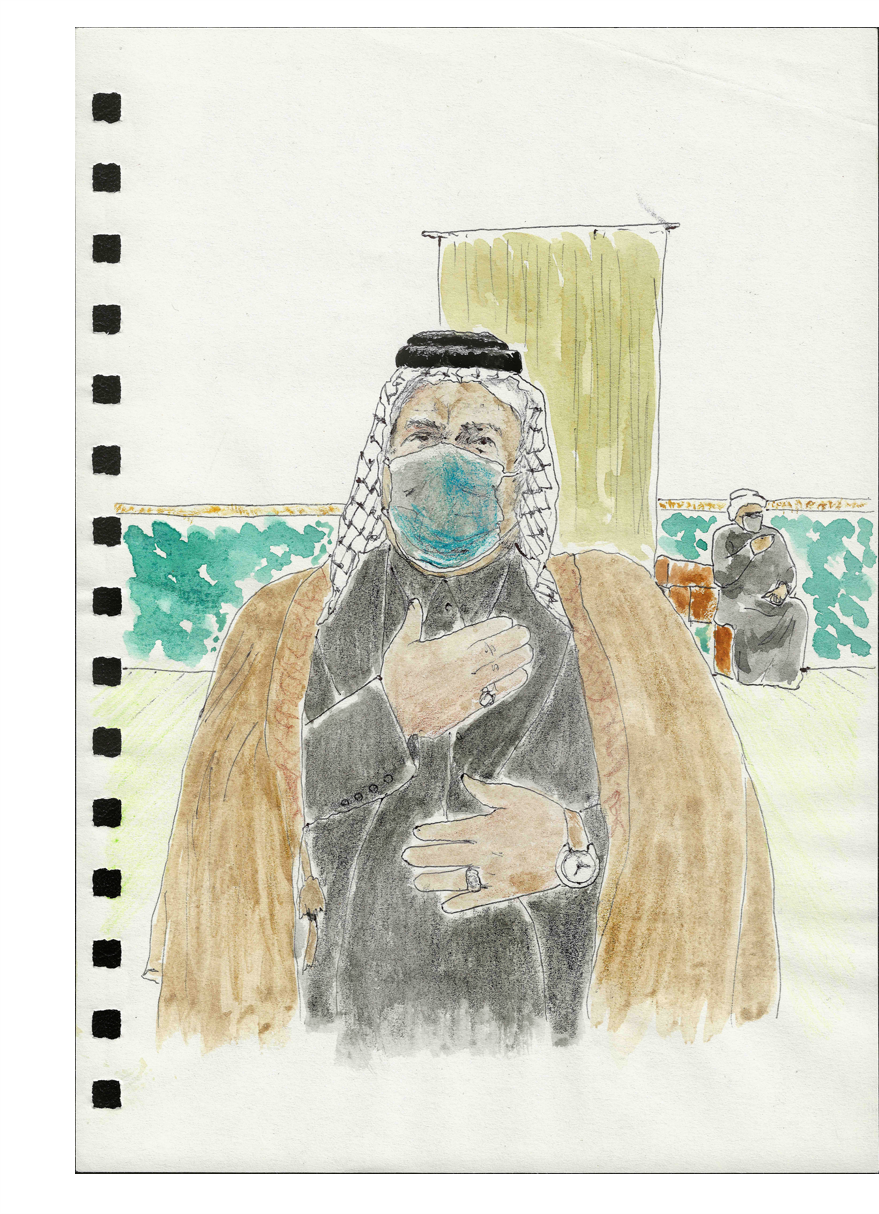

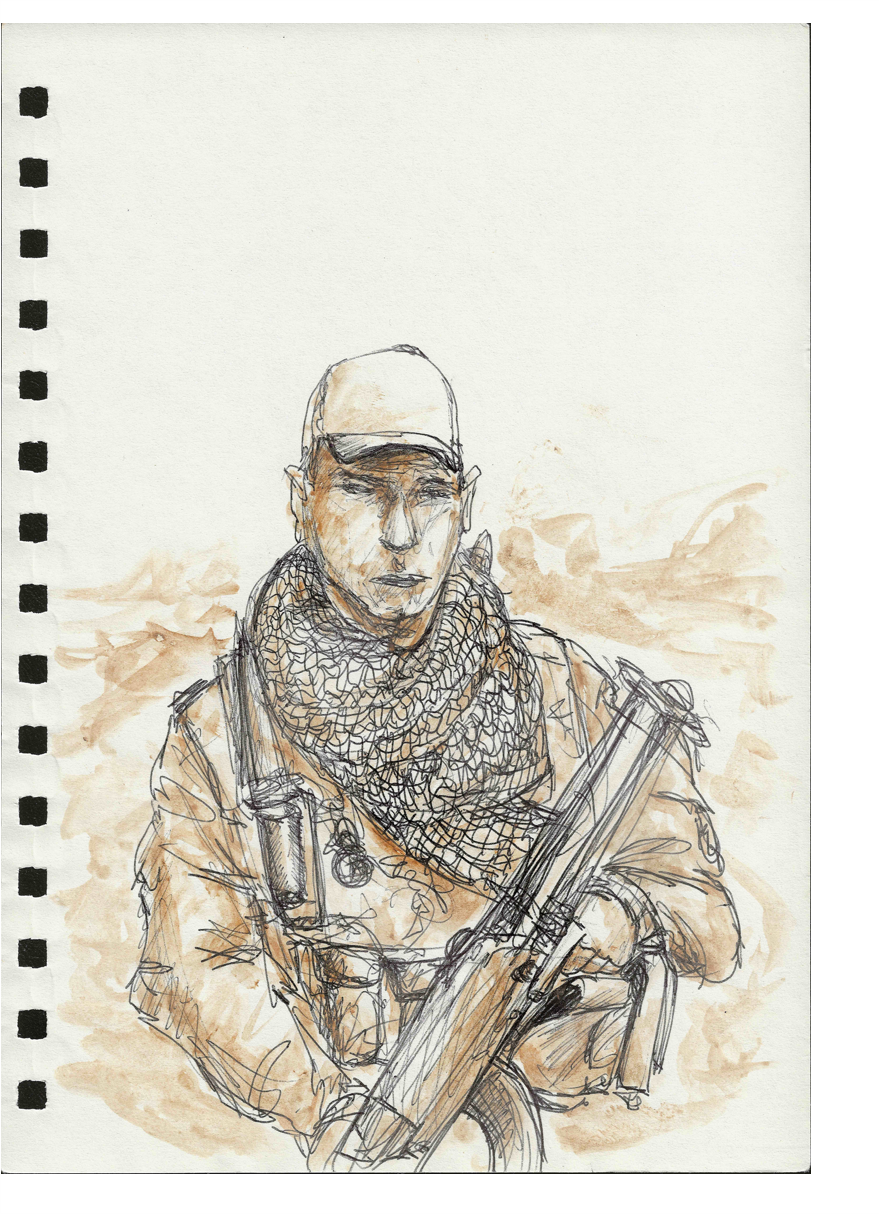

February 2021. Pope Bergoglio announces that he is about to visit Iraq, a first visit that has historical and political significance, even more so than religious dialogue. The Vatican informs us that he will visit Abraham's house in the remote valley of Ur, celebrate a special mass in Baghdad’s Cathedral and another in the stadium in Erbil. These are just a few stops on a busy schedule of events and meetings throughout the country. 2020 has just ended, the Covid emergency continues, the world is still limping along, but we understand that this will be a unique and unrepeatable event to document. With Gabriele Micalizzi and Fausto Biloslavo, I leave a week before the Pope's arrival to visit the Christian villages attacked by ISIS. They are concentrated in the northern part of the country, in Iraqi Kurdistan, in an area that at the time was guarded by the NPU (Nineveh Plan Protection Unit), the Christian militias defending the villages in the Nineveh Plains, which had been emptied of at least 100,000 people since the arrival of ISIS. In Karamlesh, a small village of low houses and dust, the bell tower of the semi-demolished church still managed to ring out for Mass. We found hospitality for the night in a container kindly offered by Father Paolo Habeeb. In the rectory riddled with Kalashnikov bullets, the black-flagged militia had cut off the hands and head of the statue of the Virgin Mary. The missing parts had been recovered and saved by a faithful parishioner who had kept them in a box until our chance encounter, when we were able to reattach everything with polyurethane foam from a construction site. The workers/parishioners decided to forego restoration and, instead, leave the damage to the sculpture visible, as if they were still open wounds for all to see.

A few hours of work, a can of interior foam, nothing complicated. Yet the faith and need of these men and women to express their pain seemed to us stronger than a certified restoration.

About a month later, we saw that Madonna again: she was in Erbil, on stage with Pope Bergoglio, who blessed her as a relic of Christianity. That plaster statue, mass-produced and of little value, has become an object of worship, tradition, and hope because of the trauma she suffered.

Many things happen during that month of travel. We discover worlds hidden beneath the carpet of conventional information, such as young people who transform verses from the Koran into lyrics to be sung to hip hop beats. We meet them in a mosque on the outskirts of Baghdad. They are tense but determined. They know they are risking a lot, as prison is the punishment for those who set the Koran to music, but this does not stop them from expressing themselves. The fans/believers standing on the carpets beat their chests hard to the rhythm of the beats, while young preacher-rappers take turns on stage, challenging each other and showing off their own style. We don't understand their words, but we understand their need to communicate very well, and we even manage to get caught up in the syncopated melodies.

They are tense but determined. They know they are risking a lot, as prison is the punishment for those who set the Koran to music, but this does not stop them from expressing themselves. The fans/believers standing on the carpets beat their chests hard to the rhythm of the beats, while young preacher-rappers take turns on stage, challenging each other and showing off their own style. We don't understand their words, but we understand their need to communicate very well, and we even manage to get caught up in the syncopated melodies.

We wonder what is reportage, what is art, what prevails and what is really important.

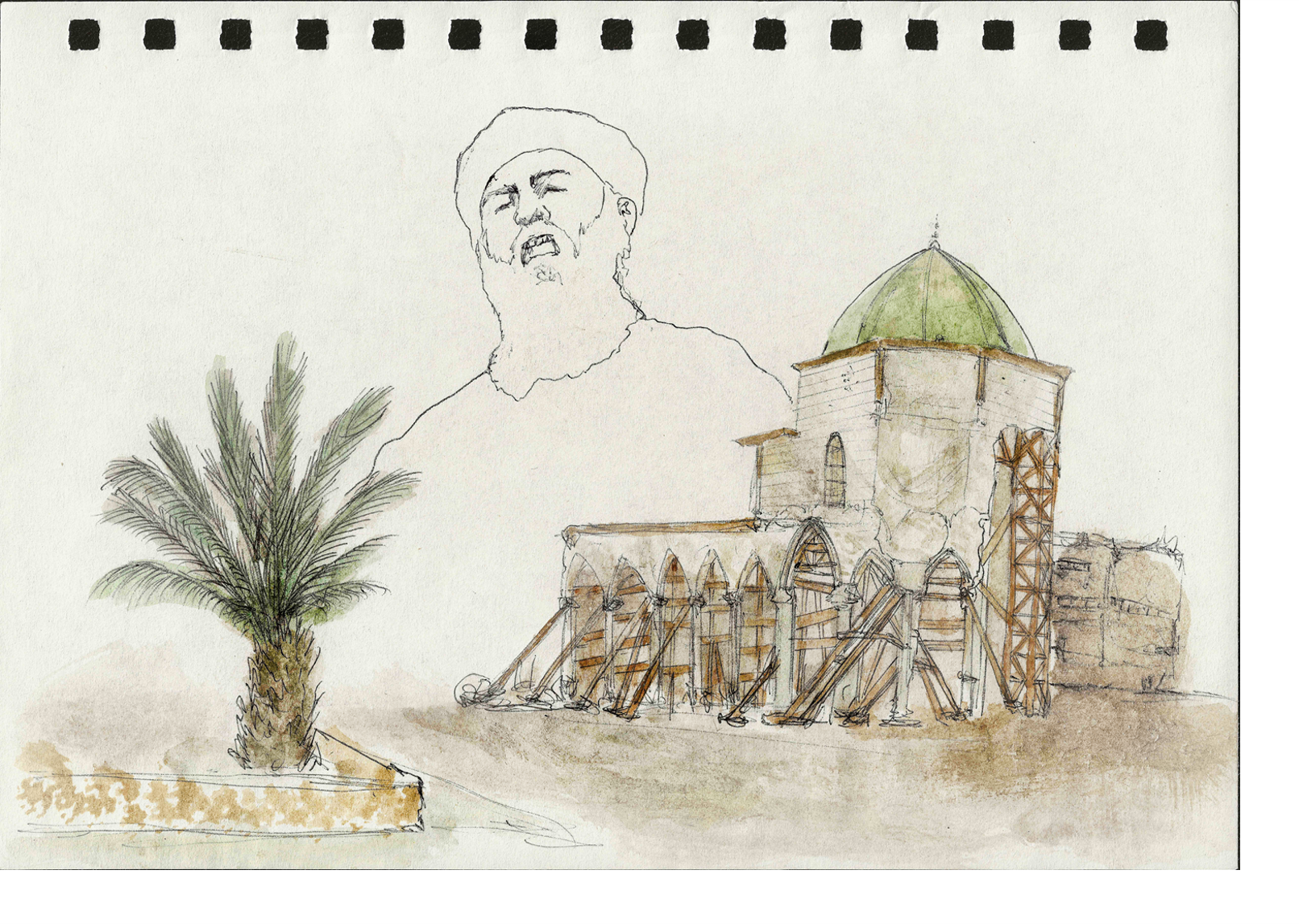

A few days later, we are in Mosul, at that moment a city in ruins, with large sections collapsed under the bombardment of the allies united against the Caliphate. We decide to go to where it all began, at least officially. The Great Mosque of al-Nuri, where on June 29, 2014, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, in one of the very few recorded occasions, climbed onto the pulpit to proclaim himself leader of the new Caliphate. A symbolic place, iconic for the Middle East and also for the West, although the latter struggles to even find it on the map.

We stop our car in front of a UNESCO construction site, an area cordoned off with dozens of workers engaged in rebuilding a structure that has been there since 1172 and was heavily damaged in June 2017 during the military offensive to liberate Mosul from ISIS. Al Nuri was built by Nur ad-Din Zangi, a Turkish leader who already called himself commander of the jihad against the invaders at the time. Before even entering, I notice that all that remains of the famous leaning minaret called ‘the hunchback’ - a kind of Muslim Tower of Pisa - is the stump at the base. And to think that for a long time it was the tallest in the region. War changes dimensions, alters heights, and erases records.

I look down, the ground is dark, a shade of brown I have never seen before. There is a small bump in the ground. I look closer, it looks like a dust-covered gun. It is plastic, a toy gun, or rather half of a replica of a black revolver. I wonder what it is doing there, on what was once a battlefield, a plastic weapon. The thought is short-lived because I only have to look up to see a huge 3-meter by 5-meter billboard warning of various improvised explosive devices that could be in the area.

And it is only then that we understand: the square of land where we have stopped, a few steps from the entrance to al-Nuri, is a children's playground. How did we not notice it before? There are even swings, rusty and with twisted chains, but still swings for children. Even the billboard is for them. Some adult has thoughtfully placed images of objects that conceal danger next to them. A puppet can turn out to be a mine, a tin box a detonator, a piece of wood the trigger for a bomb. On that billboard there is also a picture of a toy gun like the one at my feet.

The wind moves it; if it were connected to a trap, it would have already exploded, so I conclude that it is harmless. I pick up the outline of the fake gun and put it in my backpack; I need to take a piece of reality with me. That object is no more valuable than a piece of trash, and in my opinion, there is nothing more real than trash.

On our arrival in Italy, we are slapped in the face - as usual - by the reality we left behind a month earlier, which cares about nothing but itself.

In my apartment in Milan, there is a small white canvas, without a frame, showing the outline of a dusty plastic gun. There are no dates, no signatures, just that piece of trash on a white background. Every time I look at that rectangle, the same question that came to mind when I saw the rappers with the Koran or the decapitated Madonna comes back to me: what is reportage? What is art? Where does the story of reality lie?

When guests ask me who is the author of that artwork on a white background is, I always reply: “All of us.”

Salvatore Garzillo

Born in Naples in 1987, Salvatore Garzillo is a freelance journalist. Since 2011, he has been covering crime news for Ansa in Milan.  He has followed the main news stories of the last 15 years and produced reports (some illustrated by himself) in Afghanistan, Kosovo, Greece, Iraq, India, Brazil, and Ukraine (since 2014), which have been published in Italian and international media. He always has two pens in his pocket and draws everywhere, including on receipts.

He has followed the main news stories of the last 15 years and produced reports (some illustrated by himself) in Afghanistan, Kosovo, Greece, Iraq, India, Brazil, and Ukraine (since 2014), which have been published in Italian and international media. He always has two pens in his pocket and draws everywhere, including on receipts.

Gabriele Micalizzi

Gabriele Micalizzi, class of 1984, is an award-winning photojournalist who works with major international publications. His career as a  photojournalist in conflict zones began in 2010, when he documented the “Red Shirt” uprising against the Thai government. Since 2011, he has been assiduously documenting the situation in the Middle East, covering all events related to the “Arab Spring” and dividing his time between Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya, and then working in the Gaza Strip, Turkey, and Syria, where in 2019 he was wounded by an explosion while documenting the Kurdish advance against ISIS.

photojournalist in conflict zones began in 2010, when he documented the “Red Shirt” uprising against the Thai government. Since 2011, he has been assiduously documenting the situation in the Middle East, covering all events related to the “Arab Spring” and dividing his time between Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya, and then working in the Gaza Strip, Turkey, and Syria, where in 2019 he was wounded by an explosion while documenting the Kurdish advance against ISIS.